Sabine Herrmann

Sabine Herrmann

The correspondence between Giacomo Casanova and Pietro Zaguri is one of the most valuable records of late 18th-century Venice. After his final departure from Venice in 1783, Casanova kept up a correspondence with the Venetian patrician that lasted more than twenty years, full of news, feelings, irony and reflections on a changing world.

This epistolary exchange represents not only a private chronicle, but a true portrait of Venetian society in the last years of the Serenissima.

The friendship between Casanova and Zaguri was born in the autumn of 1772 in Trieste, when the two met for the first time. A few months earlier, it had been Zaguri himself-along with patricians Marco Dandolo and Francesco Grimani-who had worked to obtain the revocation of the exile inflicted on Casanova in 1755.

The intensity of their relationship grew especially after Casanova returned to Venice in November 1774, when he lived for a time in the magnificent Palazzo Zaguri on Campo San Maurizio.

This is a fundamental passage in his Venetian life: it was in Zaguri’s house in 1777 that Casanova probably met Lorenzo Da Ponte, who in those years was Zaguri’s secretary and “fellow student,” as Da Ponte himself recounts in his memoirs.

This bond between the three men shows how much Palazzo Zaguri was a place of intellectual encounters and decisive relationships for Venetian culture of the time.

After the new farewell to Venice in 1783, the correspondence became constant:about 120 letters written in Italian, spanning from 1772 to 1798. The contents range from politics to gossip, from cultural life to intimate confidences.

The letters constitute a vivid fresco of the Venetian city and society. Zaguri informs Casanova of elections and offices in the Senate, internal disputes within the patriciate, and worldly salons. The two friends exchange books, texts, literary opinions and theatrical commentary. Daily life, the running of Zaguri’s palace, mutual encounters and network of acquaintances emerge naturally between lines full of details and keen observations.

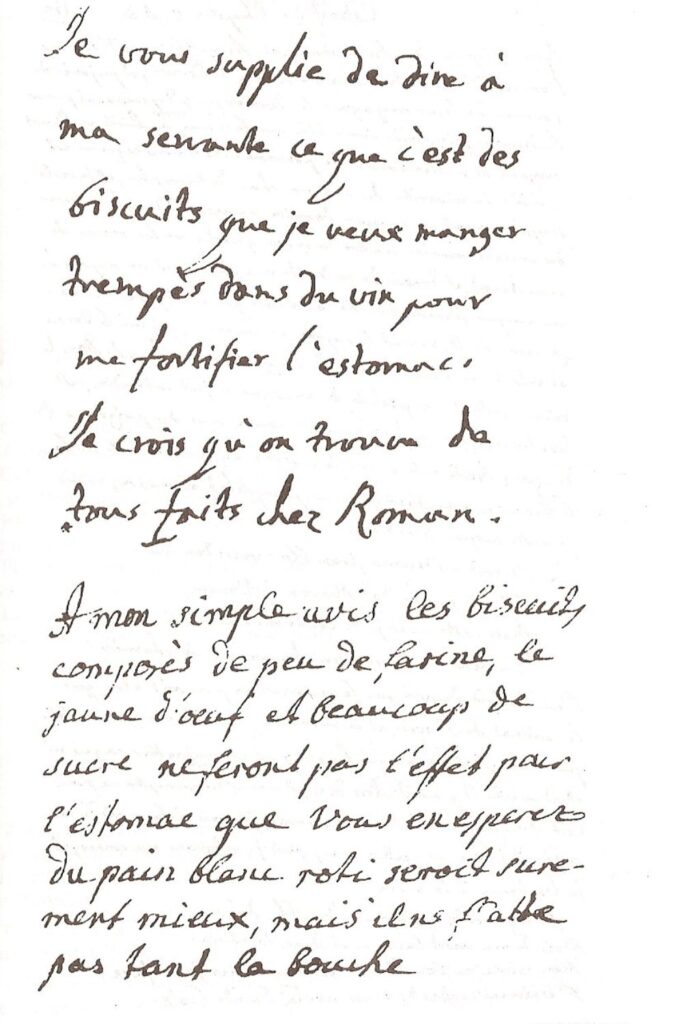

The correspondence is also extraordinarily personal. The two friends share health problems-fake porcelain teeth, recurrent gout, ear ailments-and speak frankly about their romantic relationships, jealousies, and perceived petty betrayals. The episode in 1784, when Zaguri reports to Casanova that Francesca Buschini had been seen at the “Casino dei Mongolfisti,” is famous: the news hurts Casanova so much that it prompts him to break off correspondence with the young woman for nearly two years.

The tone of the letters is often marked by irony, sometimes fierce. Knowing the freedom with which he writes, Zaguri warns Casanova not to circulate his missives, to avoid embarrassment or political problems in the still tightly controlled Venice. In a letter dated March 16, 1792, he even jokes about Casanova’s misunderstandings with the staff at Dux Castle: “I’m surprised he didn’t kill any of them!”

The historical value of this correspondence is exceptional. On the one hand, Zaguri observes from the inside the slow decline of the Serenissima, commenting with lucidity-and sometimes resignation-on the signs of political and social collapse. On the other, Casanova appears in a more reflective and meditative phase of life, committed to defending his dignity, nurturing his intellectual ambitions and keeping alive his ties with the Venetian nobility.

The correspondence is also crucial linguistically: it preserves colloquial forms, sarcasm, Venetian locutions, French interference and a spontaneity that early editions often toned down or censored.

These letters, read today, restore not only the portrait of a deep friendship, but also that of a changing world: two distant men, united by the memory of Venice, observe and comment on an era rapidly drawing to a close.

Would you like to discover the palace where Casanova actually lived? Visit the Permanent Museum dedicated to Giacomo Casanova at Palazzo Zaguri.